ON a recent visit to Karachi the prime minister announced plans to build a Karachi-Lahore motorway. The groundbreaking of the first segment from Karachi to Hyderabad was also performed. The existing four lane Karachi-Hyderabad ‘super highway’ is in rundown condition. The plan is to upgrade it to a six-lane motorway, fenced on both sides.

This is to be done in public-private-partnership, a mode known as rehabilitate-operate-transfer. Under this, a private investor would upgrade the road at his own cost and then operate it for 25 years during which the investment would be recovered, the main revenue coming from toll collection. In this way, the government says the project would not require public funds.

This is all very well on paper; except when we examine the track record, successive governments have tried and been unable to make this scheme work. A ‘groundbreaking’ of this nature has been done before. One fails to see what will be done now that is characteristically different from previous attempts. I will return in a moment to why these past attempts didn’t work. But first let’s look at where we are going with our national development priorities.

In Pakistan, the main instrument for financing development is the Public Sector Development Programme (PSDP) of the federal budget. This includes heads for infrastructure and social sector components. Pakistan has grossly neglected its social sector (read human development) responsibilities and this has led to the present problems of unchecked population growth, appalling levels of education enrolment, skills development and healthcare provision, leading to rampant poverty, unemployment and lawlessness.

On the infrastructure side, Pakistan spends little over 2pc of GDP on capital spending on physical infrastructure. This is the lowest among peer countries. A 2011 working paper titled Public Investment Program Phase-I Report on Macro-Fiscal and Development Framework by Hafiz Pasha et al (among them Saqib Sherani) observed that Pakistan remained over-invested in roads; meanwhile railways, ports and the water sector remained insufficiently funded.

With the 18th Amendment, most of the PSDP subjects and funds have been transferred to the provinces and it is hoped that the provinces will now pay more attention to the human development factor. With the remaining federal funds the priority areas would appear to be building water storage, improving watercourses and restructuring the railways.

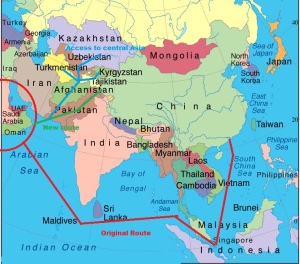

Which brings us to the question, do we need more motorways? Regional connectivity and the Pak-China corridor are important but why can’t these be built, for the most part, on the back of upgrading existing highways, building fuel pipelines and restructuring the rail system?

To date I have not seen a study on the socio-economic benefits that have accrued from building the Lahore-Islamabad motorway. Have the original objectives laid down in 1993 been met? And how do these benefits compare with alternative project opportunities that may have been available at that time? It is also worth observing that simple things like the new traffic policing systems introduced in Lahore and Islamabad in recent years have in fact brought greater everyday life and economic benefits to the citizens of these cities than the motorway.

According to the Pasha-Sherani report: to ‘crowd in’ sustained private investment requires more than just a high level of public investment in physical infrastructure and development of human capital. It requires the government to play its role as an ‘enabler’ (or facilitator) in the economy, by providing the appropriate institutional framework, including laws and regulations, such as guaranteeing property rights, providing for contract enforcement and dispute resolution mechanisms.

In this way, the tough laws on cheque bouncing for instance, may have had a more palpable effect on the economy (by building trust in economic transactions) than the building of expensive flyovers.

And that also explains why previous attempts at upgrading the Karachi-Hyderabad ‘super highway’ under the public-private-partnership mode have failed. Why Reko Diq turned into a fiasco. And why Pakistan Steel and the Railways continue to languish.

Recently Finance Minister Dar has spoken of the need for a ‘Charter of Economy’, a minimum economic agenda that may be agreed by all political parties to repair Pakistan’s serious economic dysfunction. One of the bullet point items on that agenda ought to be the determination of national development priorities governing the use of PSDP funds. While the provinces can focus on human development, the guiding principles for the centre should be to focus on schemes that will kick-start growth, bring about equitable distribution, improve productivity, create a high multiplier effect, and crowd in private investment. If we look around, are the motorways the best schemes available to do that? Or can we identify others?

2015 – Dawn Media Group